I met some painters from the Kano School; that is also their family name. These artists made great effort to visit Nagasaki and see the Portuguese coming off the ships; they painted and sketched the events for the Emperor. Our Japanese translator and others in attendance treated them with great deference—it was clear they held a high rank in society. Imagine being paid handsomely to create images of the Emperor’s lands; it makes me laugh to think of the Portuguese King admiring my poor drawings.

One artist, named Kano Kaizen, was reserved and polite after meeting us, in a most Japanese way; his companion however, remained openly curious about our skin. His prodding of Fadrique’s dark hands became tiresome after a time. The other artists in his group tried to redirect his attention to a discussion of drawing and painting. It is not the first time this has happened. Some in Macao had a similar reaction, as did we. Smile, then quietly deflect.

These painters mainly use a wooden brush and black ink called sumi; it is prepared in a special way from a dry stone, rubbed with water to make their inks. This block would be especially useful to me on the ships, but mastering this brush is another task I must take up.

Perhaps Yousoke can show me some of the basic techniques.

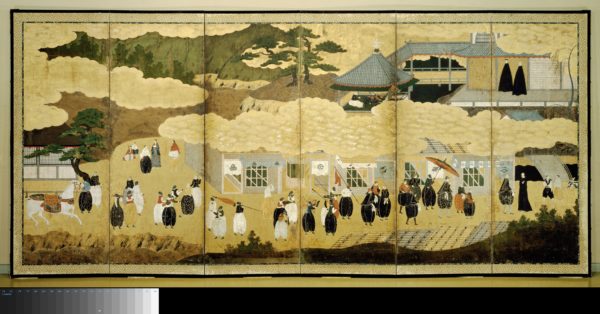

I showed them some of my drawings, and they were overjoyed at the detail and my ability. Through crude sign language and our jurebasso, or interpreter, we had a long discussion on Portuguese painting, though I only knew some small details. I was fascinated to hear about their methods for crushing and preparing their inks, and how color was applied to large walls and movable doors, called biobu and fusama. Often painting directly on gold leaf, they use it instead of pigment or underpainting.

I managed to trade a few drawings with them for a bit of Japanese paper and inks, which are of great quality compared to what I brought from Portugal and found in Macao.