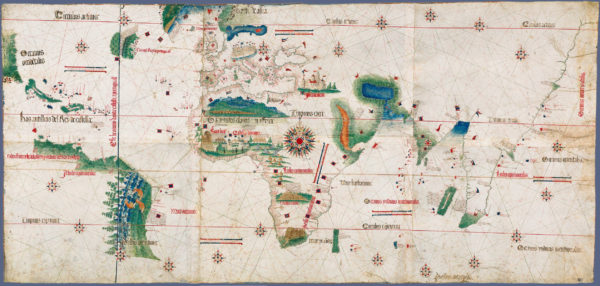

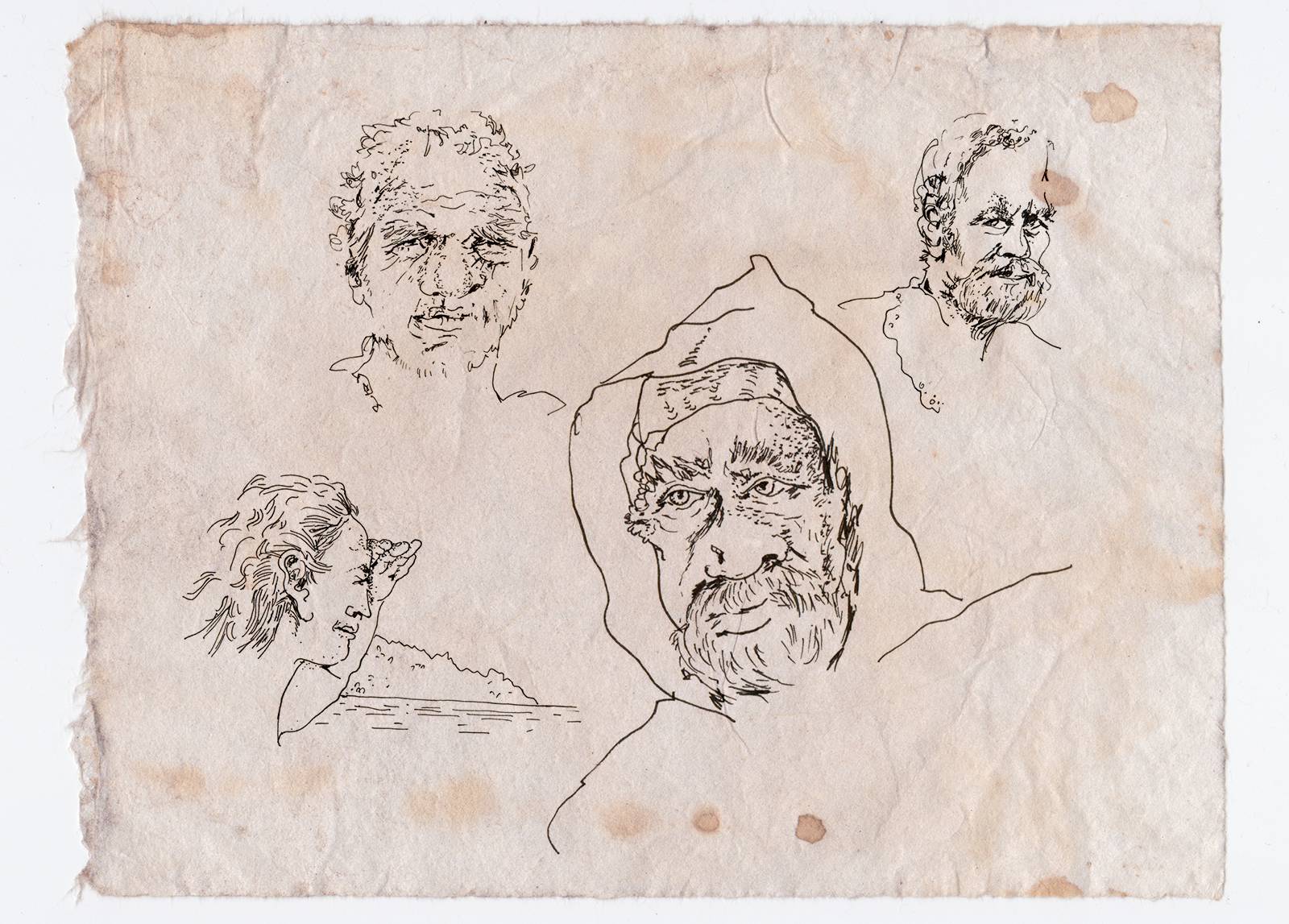

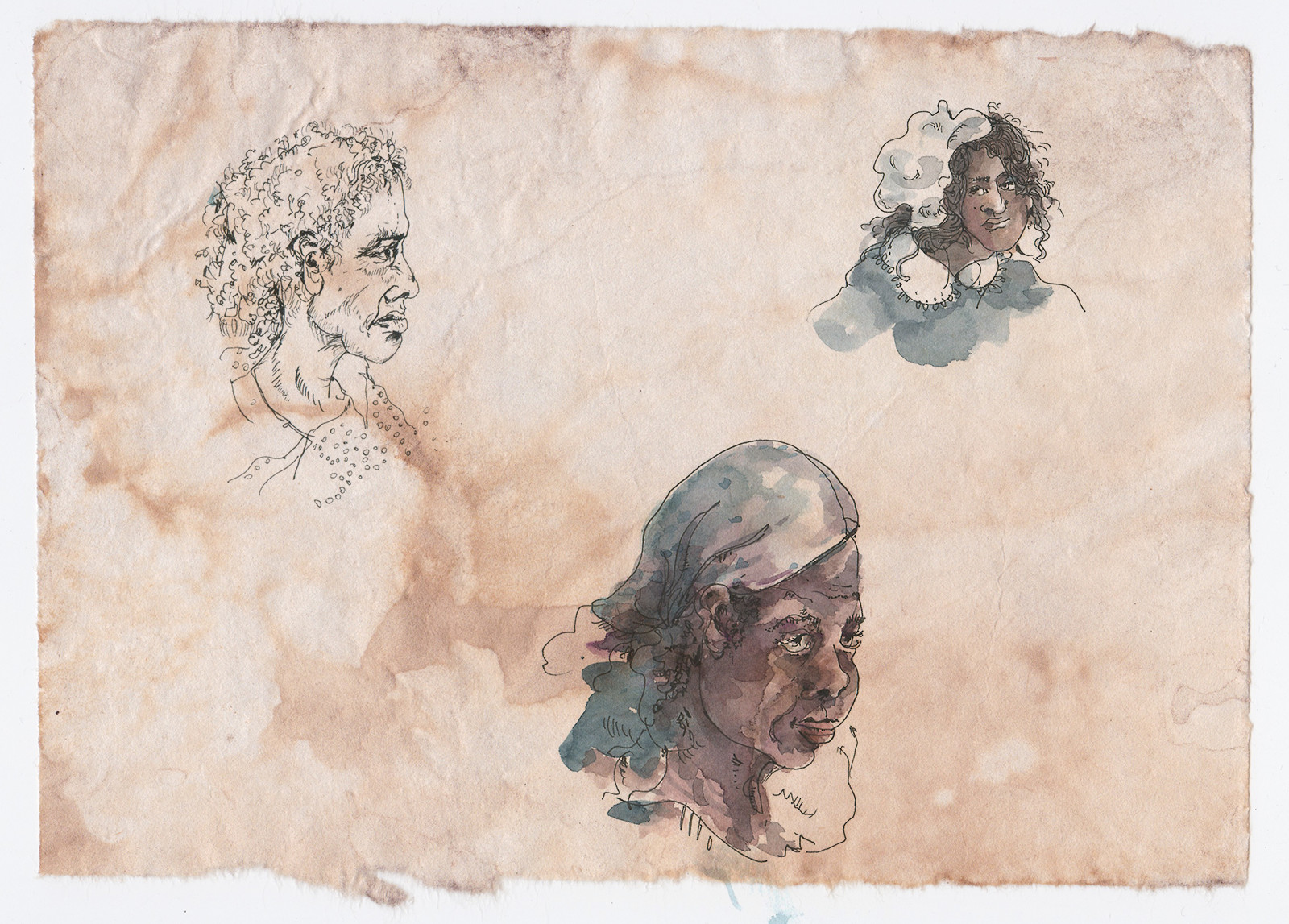

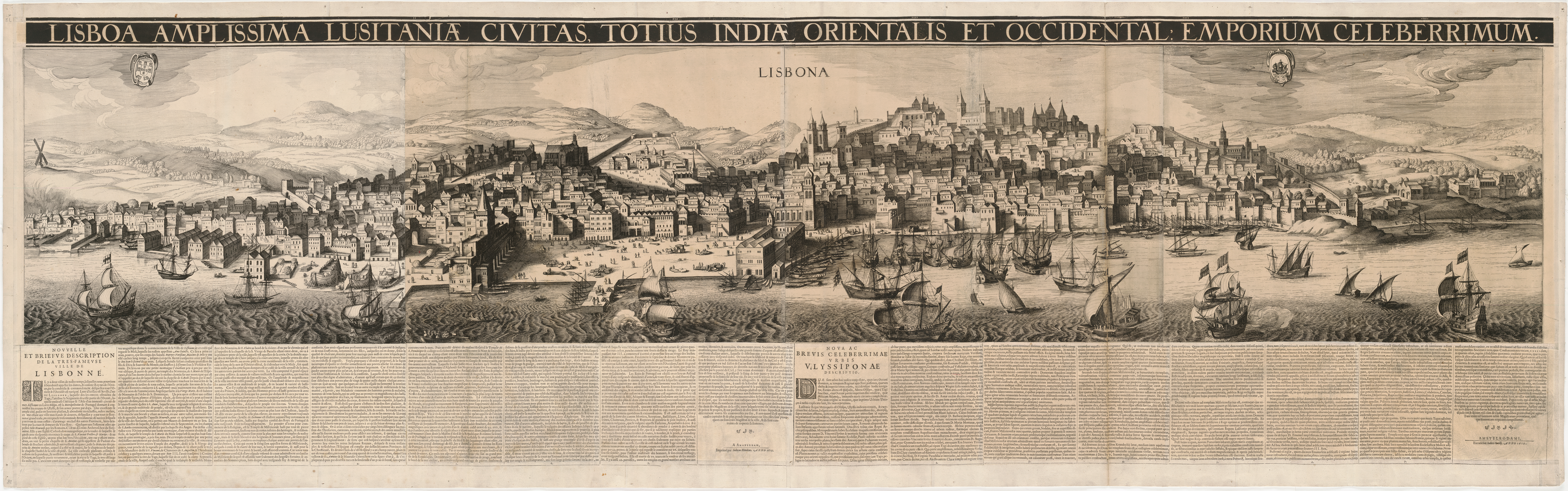

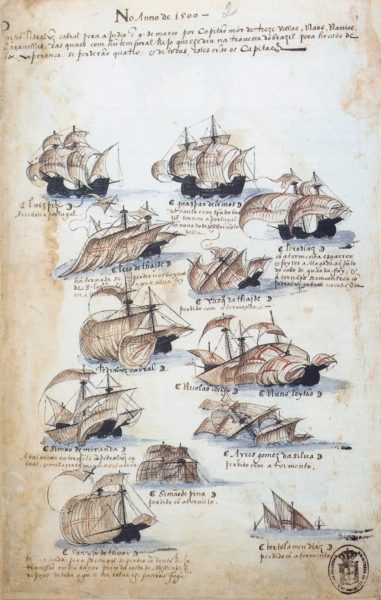

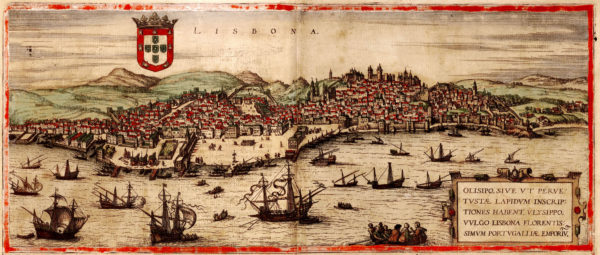

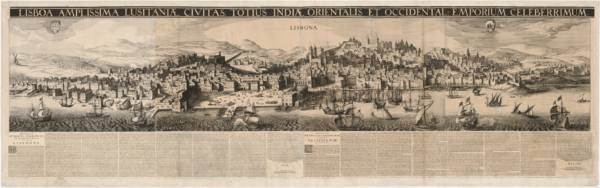

Once, only the ocean would have me. So much time has passed, and until now my time in Japan has been one of quiet labor, safe from drowning or shipwreck. My life started aboard Portugal’s ships. They gave me a chance of escape, and brought me to the shores of Japan, this strange and exquisite island. Along that strange journey, I have written down my story, and the stories of others; I have filled my books with drawings of my sailors. Lashing my fortunes to Portugal’s ships has given me life.

Perhaps the water still calls out to me, even here in Nagasaki. This diary is an illustrated account of my travels–my memories as a young man, as a navigator, and finally as a captain on a trade mission to the East.