We left Cochin in the morning, under a grey sky. The lascarim signed to our ship felt the tension among the sailors and crew, and took pains to stay out of the way. In any case, some of them did not speak more than a few words of Portuguese; perhaps that was for the best, because of what happened next.

That evening, after a rough line east, we cooked our meagre meals on the deck and began preparations for the night. The captain, in his infinite wisdom, decided that the day’s rations were to be cut after one of his dangerous commands was ignored earlier. After all the long days at sea after Mombassa, our dead friends, and furious sun and rain beating down on us day after day, cutting our food rations was too cruel. But it was fortuitous. We were looking for any excuse to abandon him—after all this time, we needed only lead the cow to the slaughter.

The captain is usually too sick to walk. He gives orders from his cabin, telling anyone who will listen that he was chosen by the King to lead this mission. The men laugh at him. Some have asked me, discreetly, how long he can continue to claim the captaincy in that condition. Vassallo was red in the face as he hobbled around, looking for a challenger to his order. My men avoided his eye, but looked to me to navigate this treacherous water as well. They knew I would not contain my anger forever. As is custom, the sailors and ship-boys split into three groups between myself, the Master, and the Under-Master to eat.

While we bent over the cooking pits around the mast, I quietly gave the signal to Abrão to set our plan in motion. For some time now, my men had been speaking quietly with the Africans, the sympathetic Portuguese, and others among the crew who felt Vassallo was unable to continue. We knew it was time to act.

A choppy sea mumbled under an overcast, moonlit sky. It was enough to mask our movements and whispered commands. We pretended to sleep, some men on the decks and others below, hands near stored weapons; they were mostly knives, axes, and pikes. Later in the night, a small group of us rose quietly; moving past snoring soldiers, we woke the trustworthy ones. The weapons were handed out. Some others we took from the sleeping soldiers. And so we took the ship.

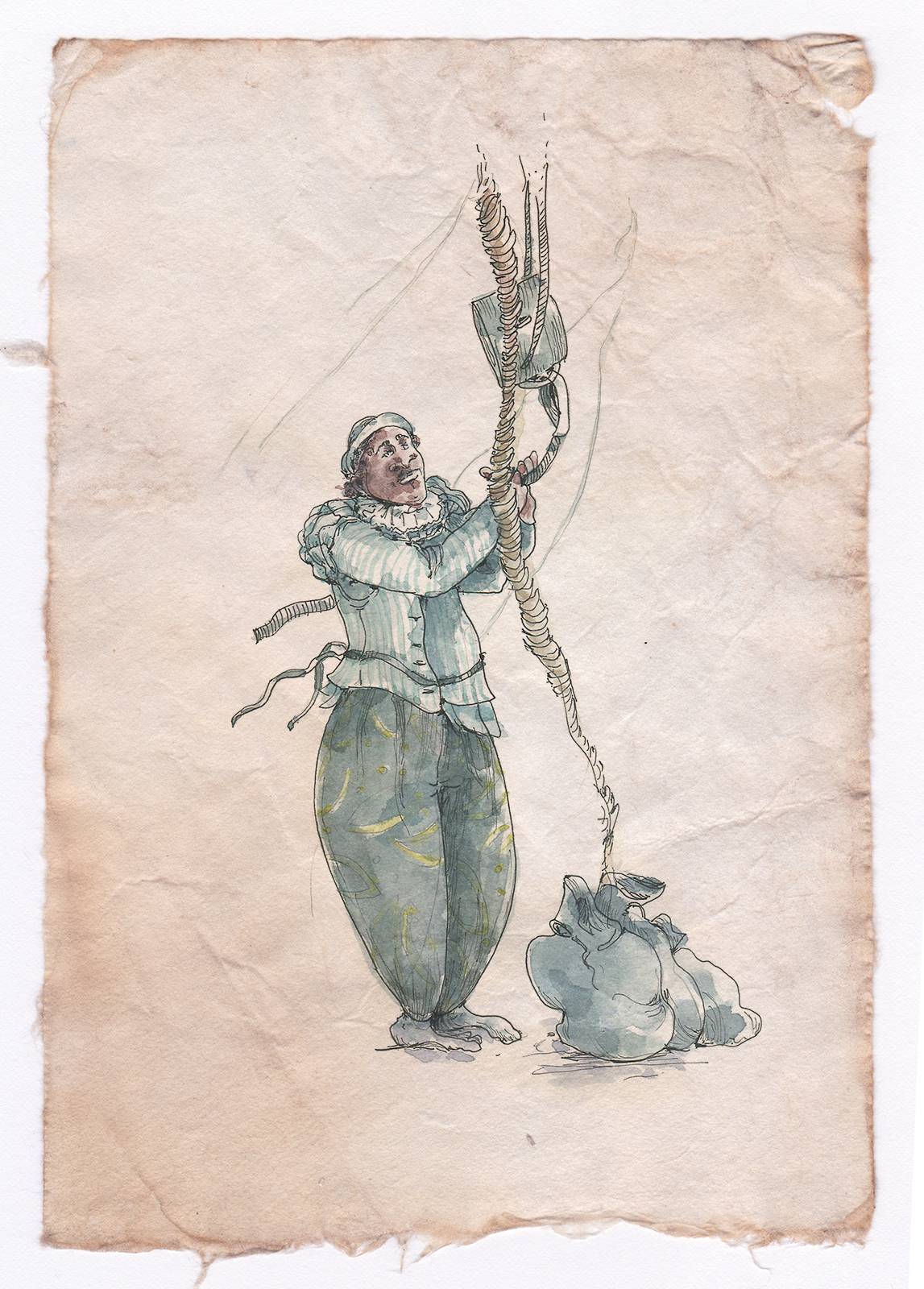

The São Catarina groaned. As if preordained, a sickly moon broke free beneath the low clouds. We walked, first quietly, then forcefully, to the Capitão’s cabin in the stern. Tirstam Duarte Gonçalves was the first to the cabin; a large man, he burst through the door in front of me. As if part of our mutiny, the sea surged beneath the ship, fighting to be heard. Somewhere behind our clotted group, rigging snapped tight; men shouted. The sound of the water fell away, and then the moment of confusion was gone. The Capitão woke to the commotion, groggy and still angry, reaching for a knife. Gonçalves fell upon him; after a few blows, he fell silent.

In the next hours, a cold peace returned; the São Catarina is now under my control. The men have consulted and elected me captain. Those few remaining dissenters have been convinced, through careful threats and promises, to take our side.

An argument over rations became a battle for the ship between those loyal to Capitão Vassallo and the men loyal to me.

Vassallo should have seen his side was lost, but he was sick and blinded by pride. The man would not admit an African could best him so thoroughly, this far from safe harbour. I gave him no choice. My men have been sailing with me for years; our bonds are deeper than his measly portions of liquor or biscuit from Neves the escrivão.

Today we buried Capitão Vassallo and de Veigua at sea. Some of the men standing near the Jesuits crossed themselves; the others spit into the sea.