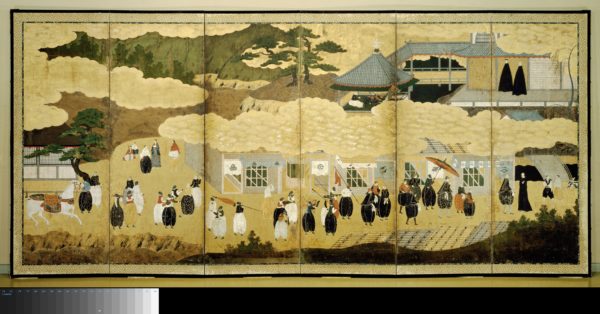

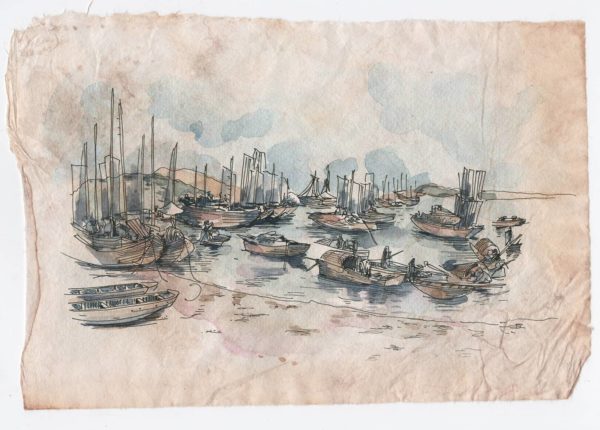

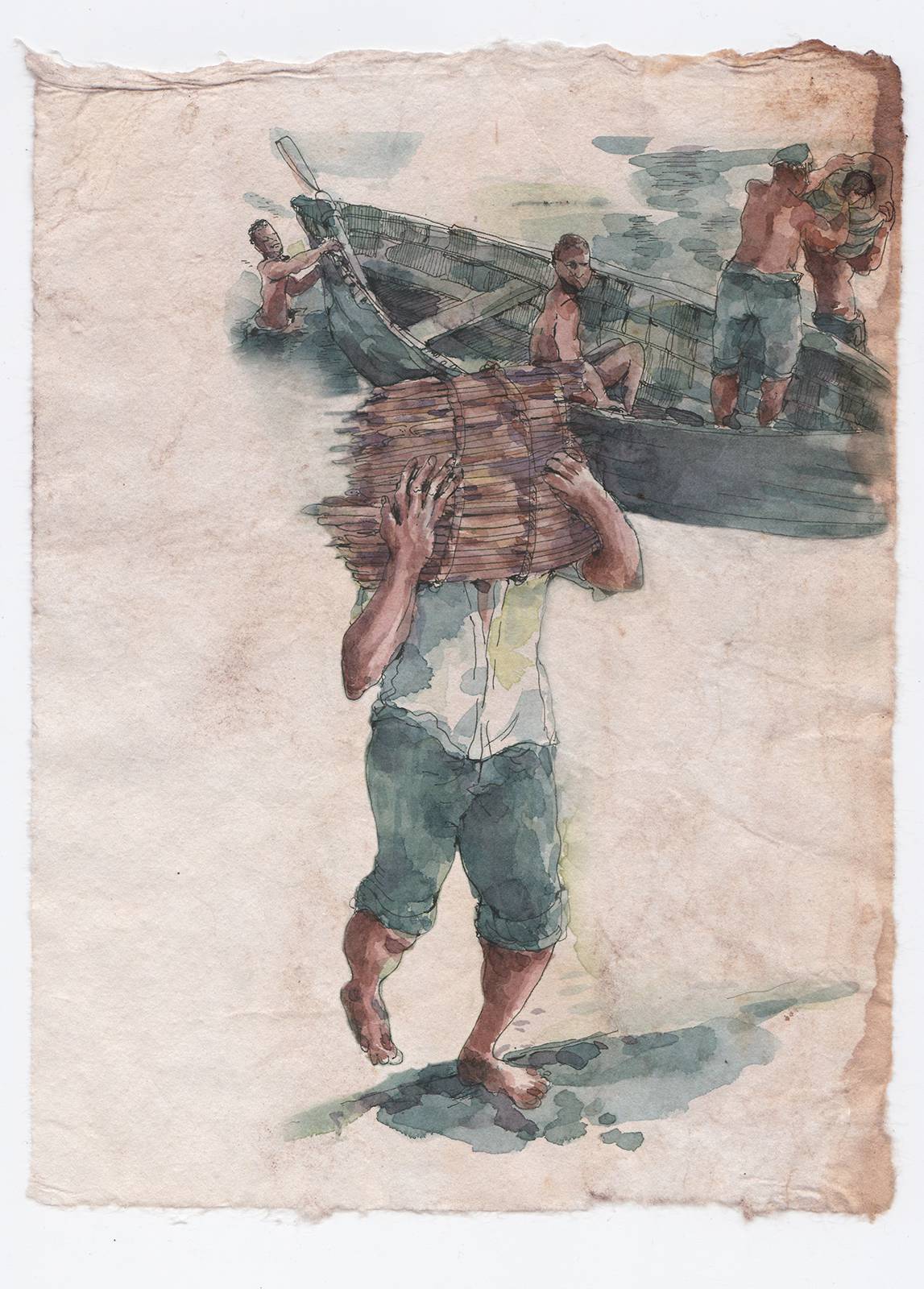

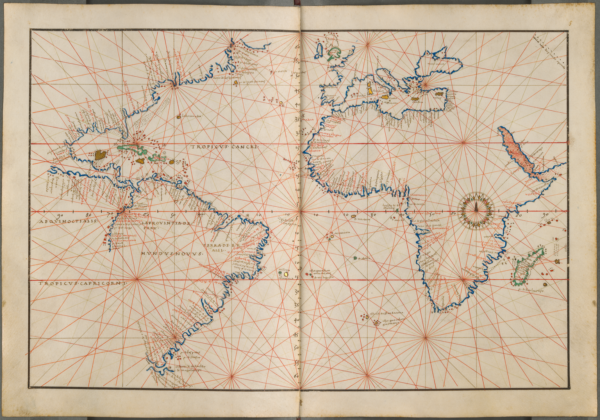

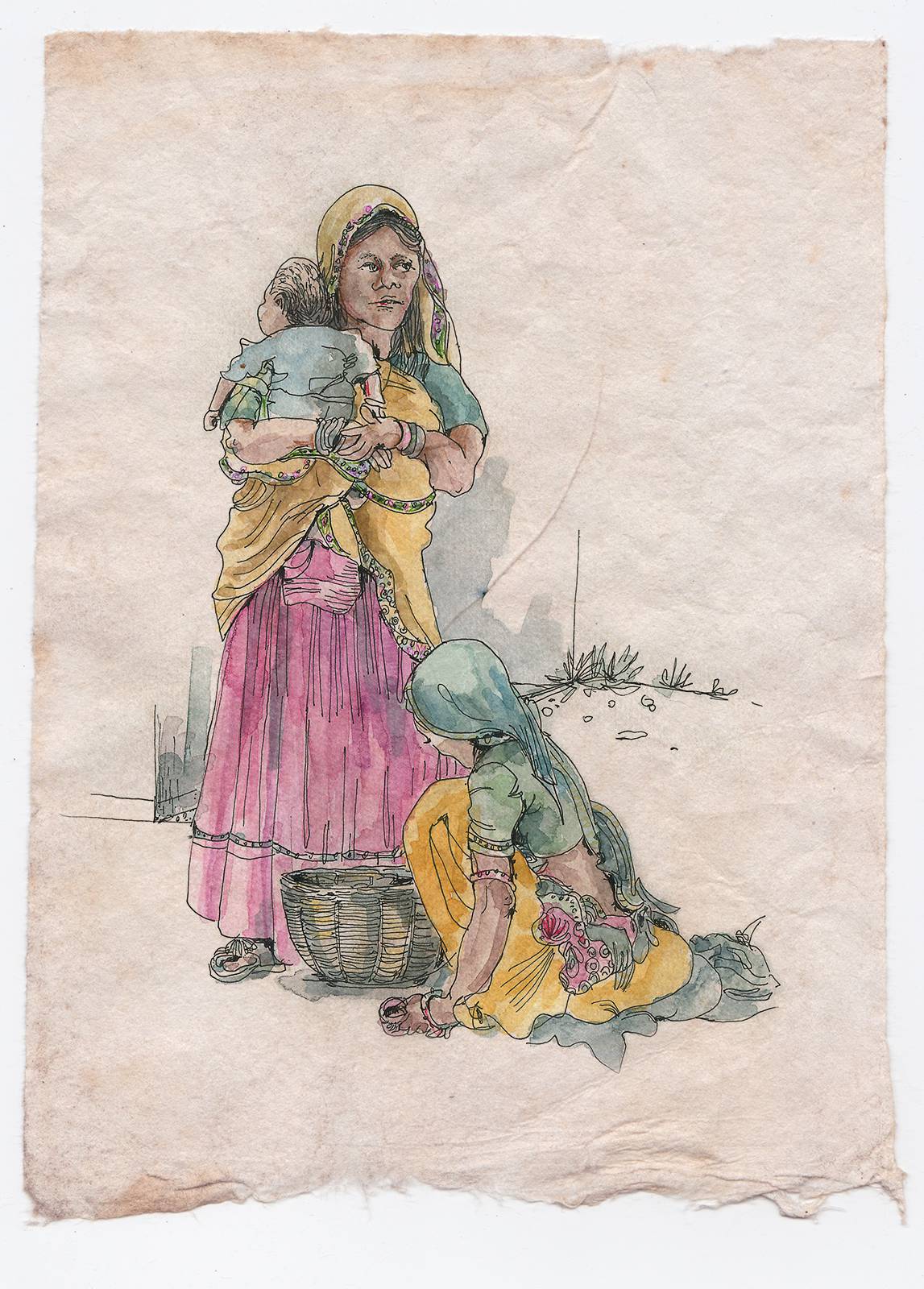

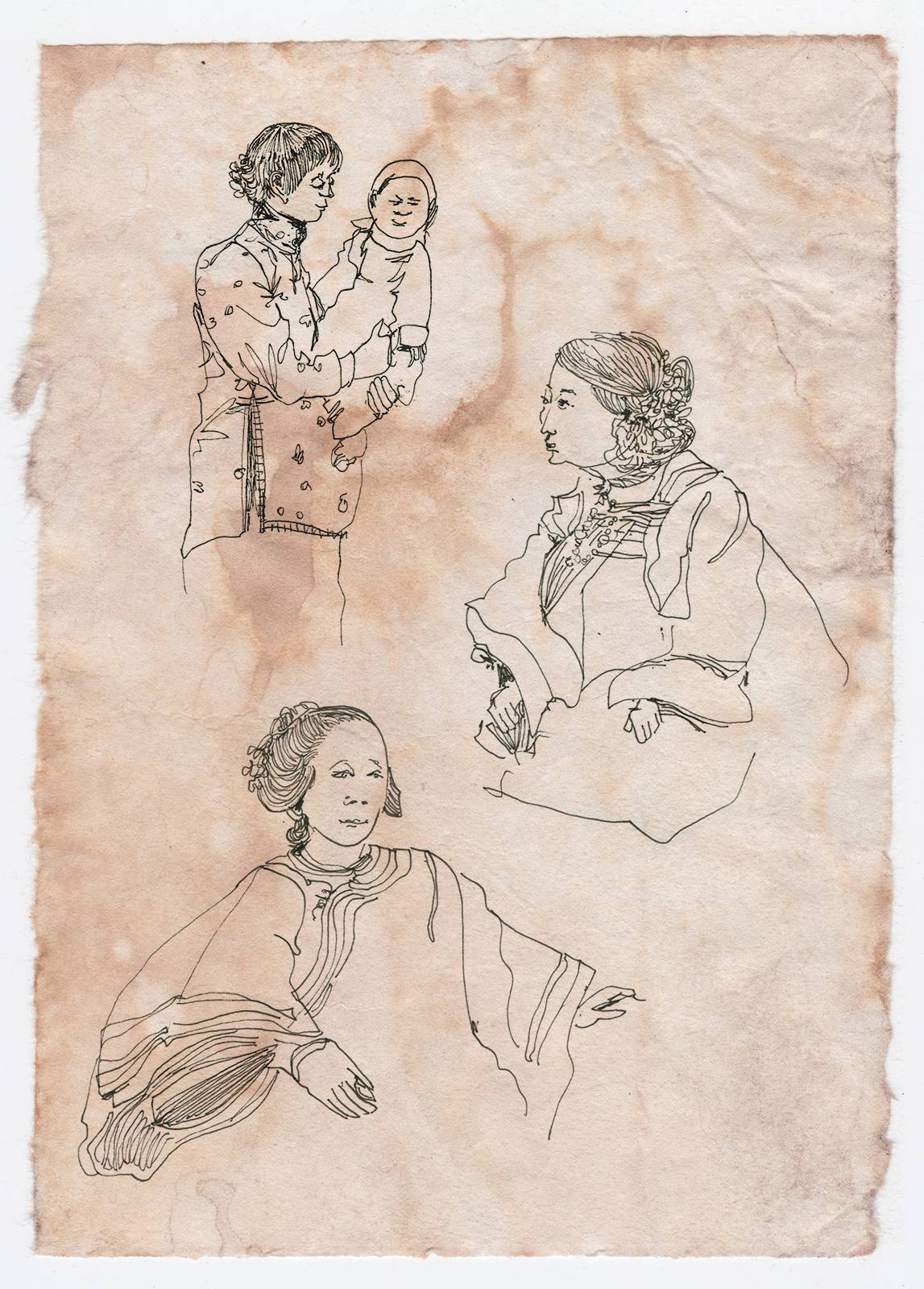

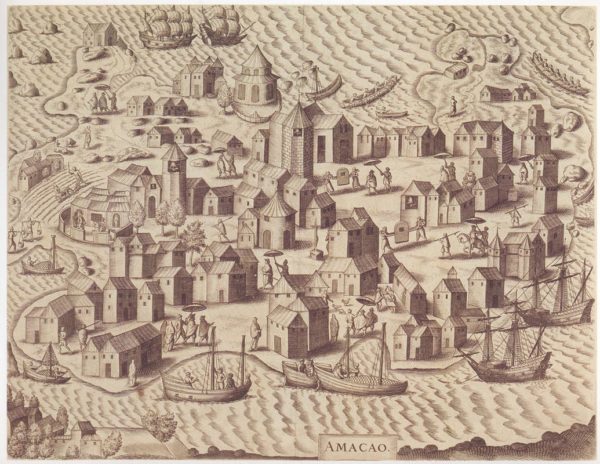

The ships I navigate on carry a mix of outcasts. There are many African men, freed and slave. There are also white Portuguese, and the occasional Moor. Other ships carry Chinese, Indians, Persians, men from the New World. What name do you put to such people?

We have clearly separated jobs and roles on this ship; I will try to explain them.

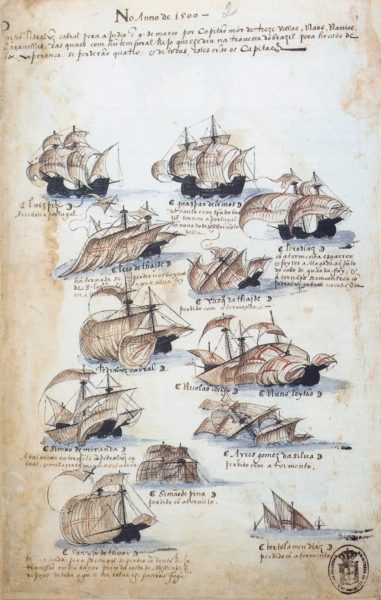

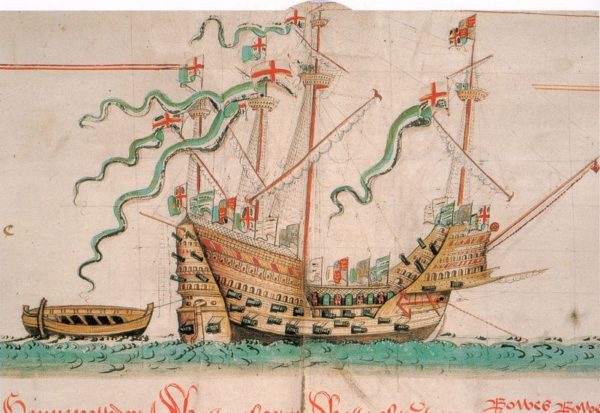

The captain is responsible for the command of the ship. These men are chosen by the Crown, many times after they pay for the title with large sums of money. In the case of Vassallo, these captains are often unqualified and poorly fit for life on the water. Only greed motivates them. Capitão Vassallo bought his way aboard the São Catarina; he has little experience managing a ship of this size.

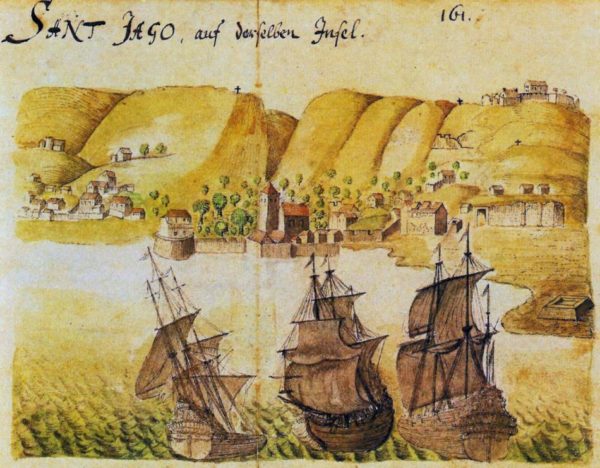

Rather than understanding his place as a figurehead, Vassallo has already begun to argue even my small navigation decisions in front of the men. My navigation skills, ones he praised when we met for the first time in Lisbon, have mysteriously become useless and incorrect. The argument is his right as captain, but what kind of man has not the sense to let his piloto navigate? We spend much time negotiating with him over every small course correction; others have begun to comment on his actions, his forgetfulness, his unsteadiness on the deck. I think this will be more problematic as we continue. The São Catarina is still afloat; our bow is headed towards the East.

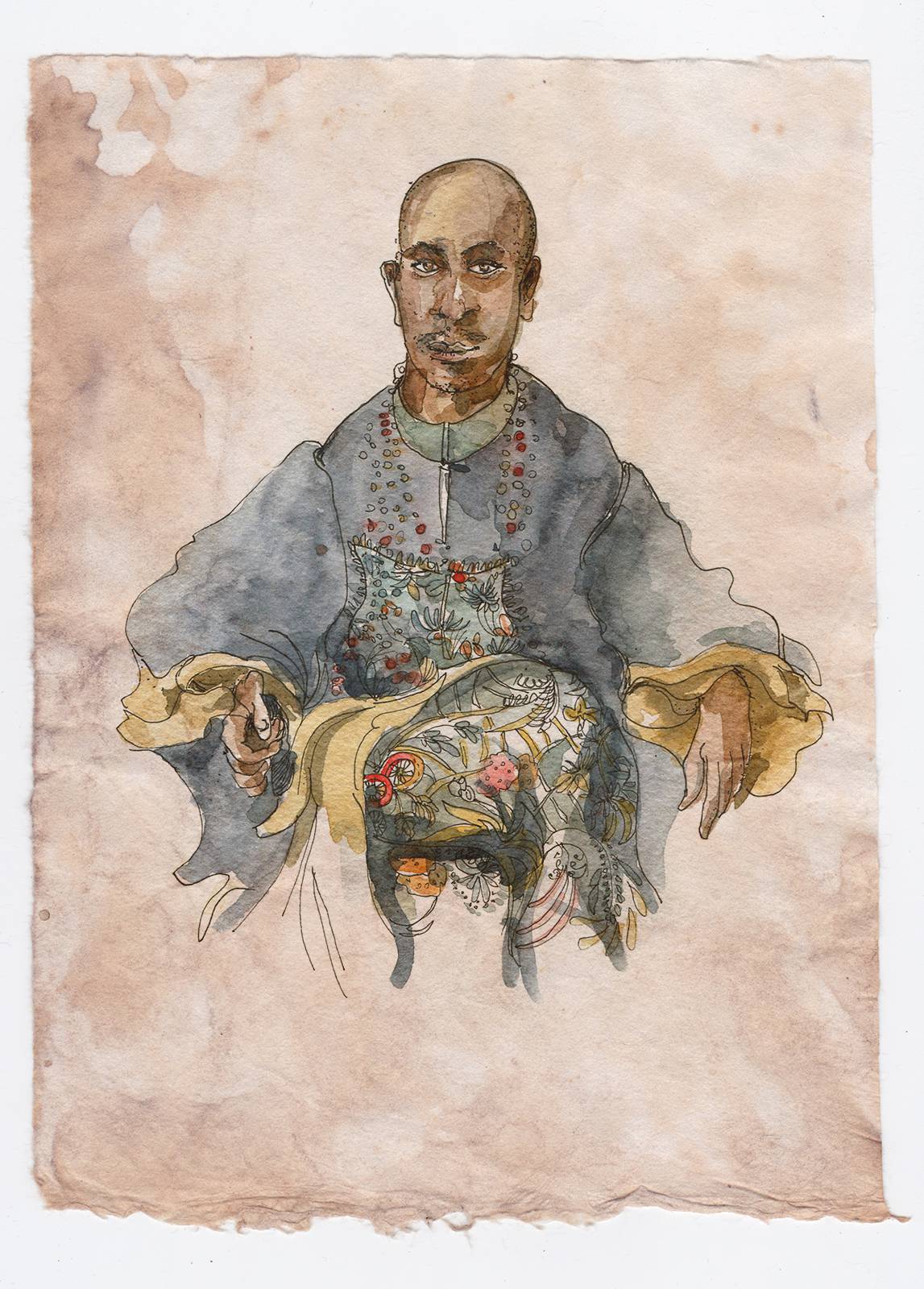

After our much-beloved captain, I am second in command, the Piloto; responsible for the navigation and functioning of the ship. Next to me is my soto-piloto, de Sousa. He assists me in all matters, and watches the compass when I cannot.

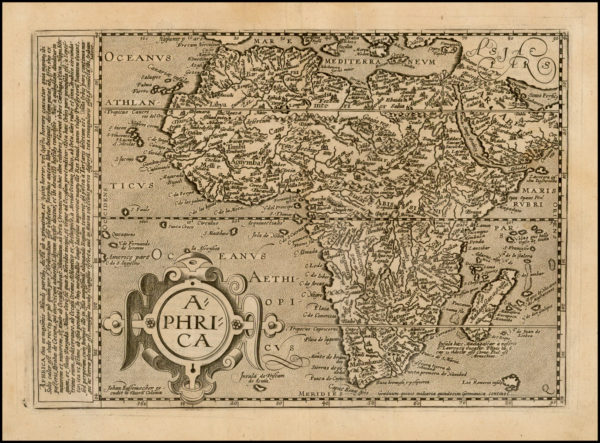

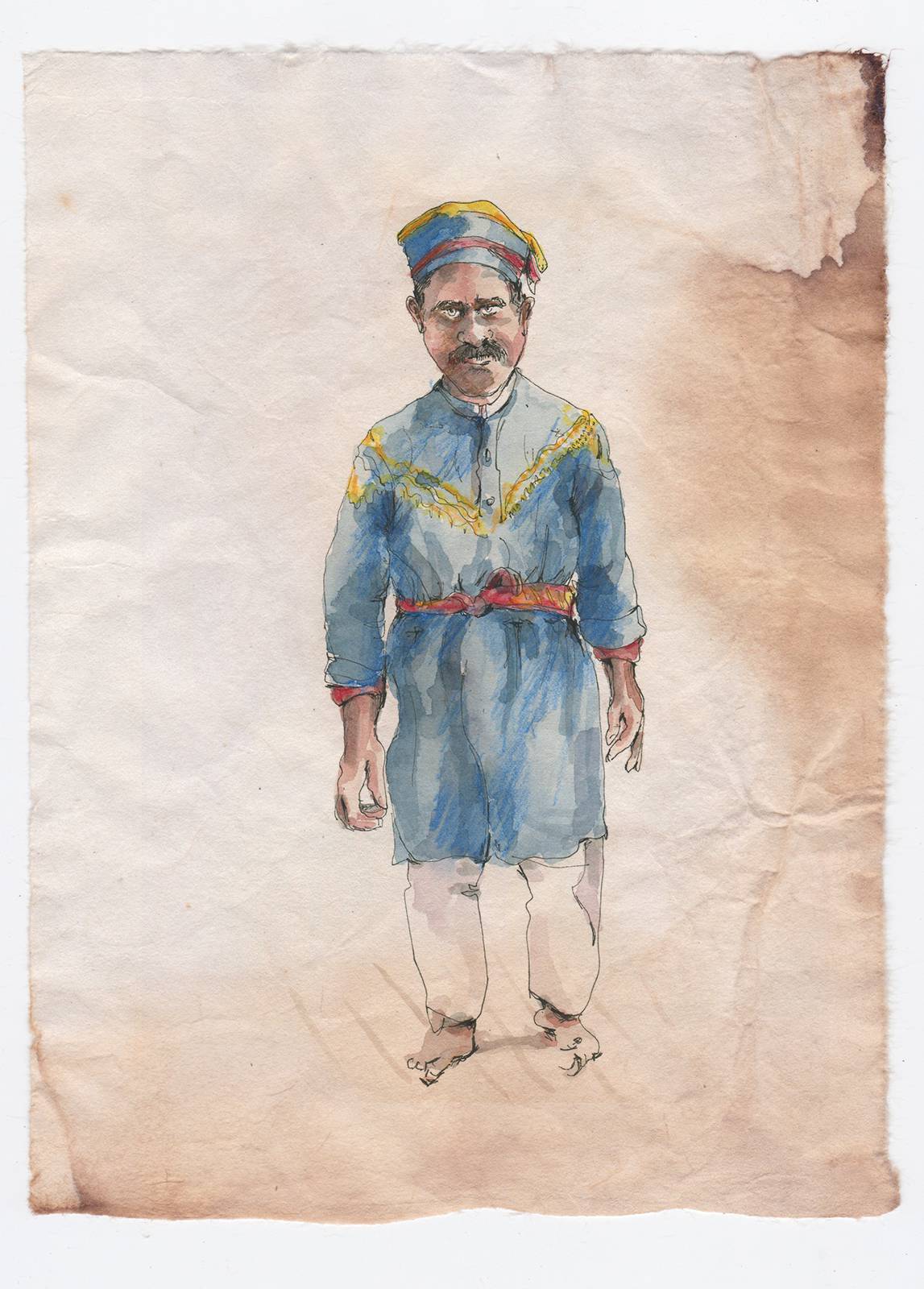

The Master of the ship is Vassallo’s man, Fabiam d’Amota. He and the Under-Master, a nasty, rude man named Jorge Paez, are in charge of the sailors, and the cargo. We give each other room, but he resents me for being black, for being a man over him. His skill with navigation and reading maps is too poor to be worth much on the compass, and despite his entreaties for me and de Sousa to train him, we will not give him help.

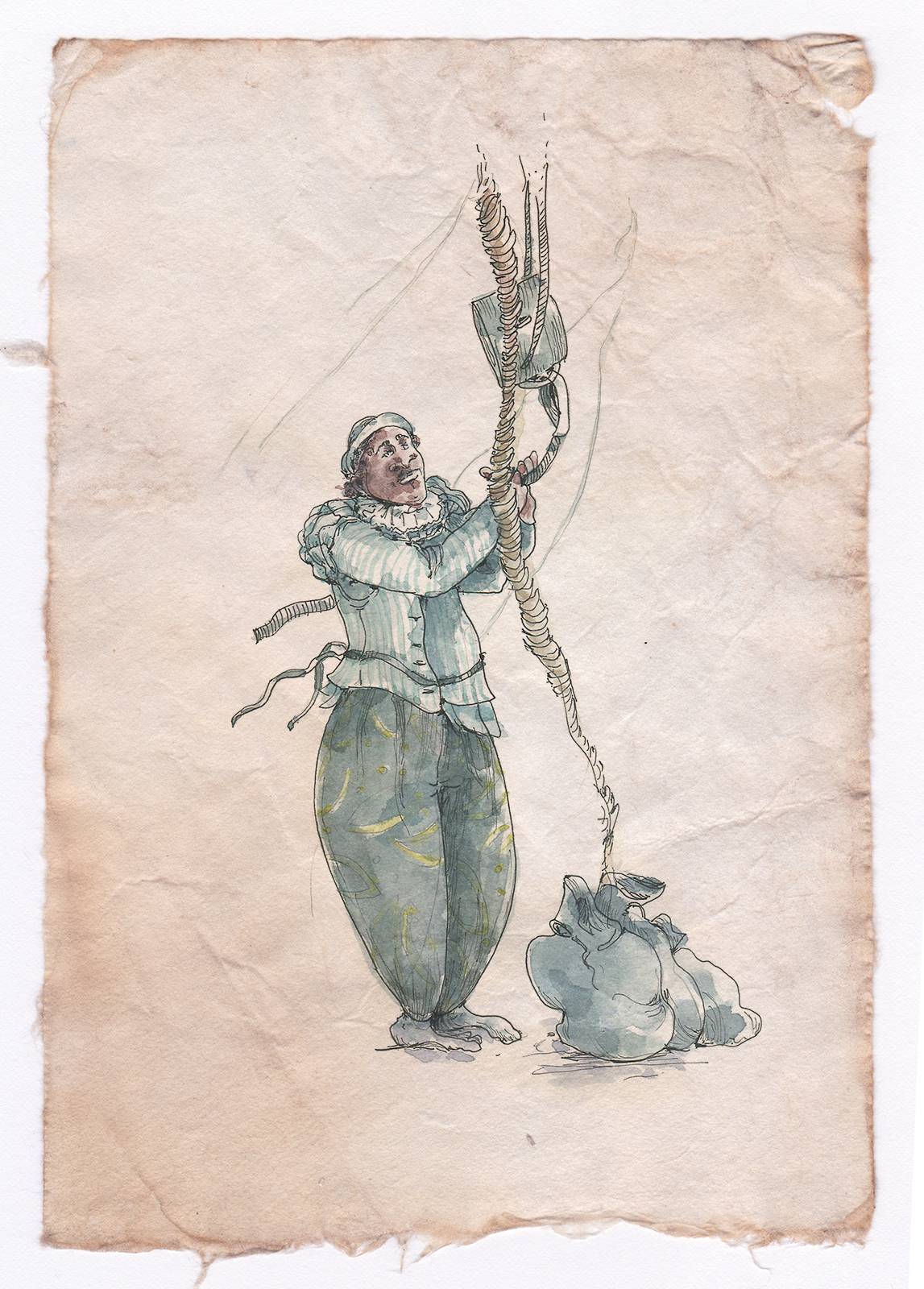

The Boatswain is Vincente de Brito. He looks after the rigging, anchors, hull, and other matters on the deck.

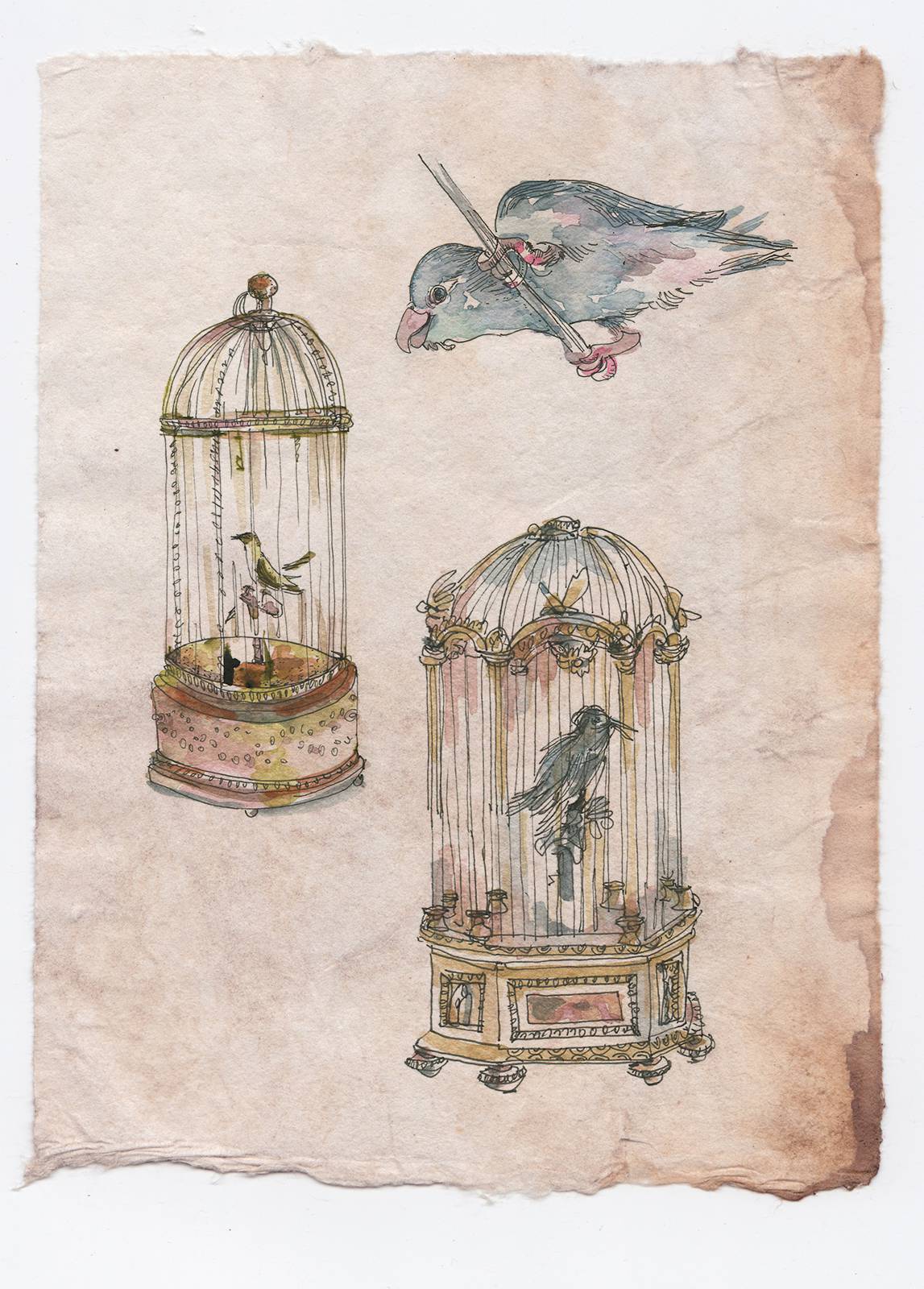

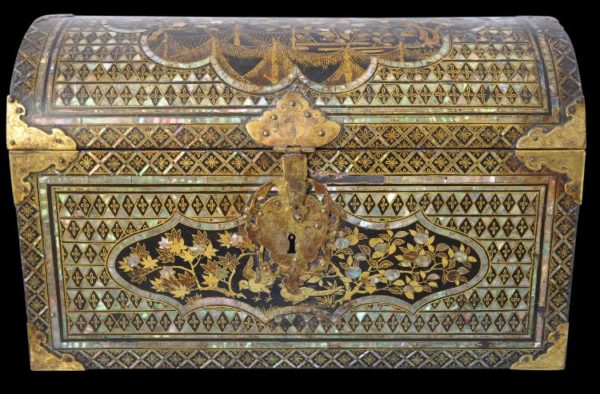

Next comes Neves, the Escrivão (Clerk). Neves is in charge of all records. He takes an inventory of our foodstores, possessions, and cargo at each port. Neves and Vassallo are old friends, and Neves makes sure that the captain’s cargo goes untouched. He watches us constantly and hardly does any work on the decks. Instead, he sticks close to the hold and the food. Neves detests my reading and writing. The man sometimes sneers when I am drawing pictures on deck, and has asked the other men about my books. Does he feel threatened? When we must speak about ship matters, I make sure to entertain him with jokes and stories to remove suspicion of my motives, even briefly.

The Guardian (Quarter-Master), runs the grumets (ship-boys). It is a wonder how he manages to stay outside at all times, in all weather. His endurance is legendary among the boys, and they would follow him over the side of the ship if he asked. His crew takes on all sorts of dirty tasks whenever he yells.

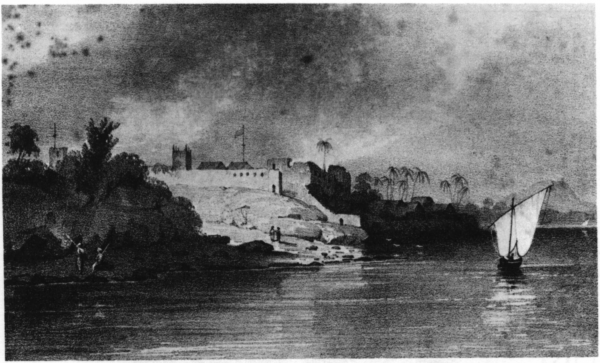

We also carry Men-of-Arms, soldiers destined for our forts and holdings in India and the African coast. The Portuguese among them are paid well for their abilities, and many have other technical skills besides fighting.

The sailors are the most numerous among us, and the roughest. So many of them are unskilled fools, given to the ocean life by accident, trickery, or bribery. The best sailors are only interested in the shorter Brazil voyages, and in returning home quickly. We must often pick up new crew members at our ports, and I have also seen captains visit the jails and prisons to recruit more unwilling hands for their voyages.

We also carry store-keepers, stewards, the marinheiros, Bombardieros (Constables), priests, and their pages. It is a crowded affair.