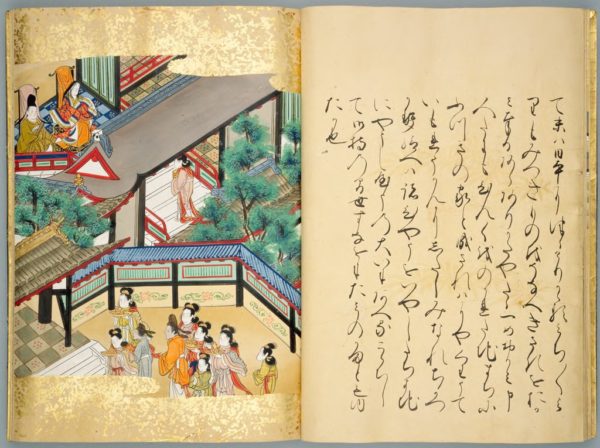

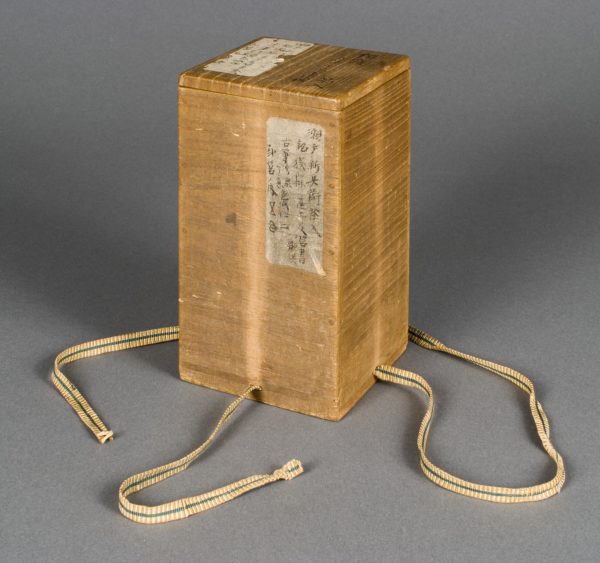

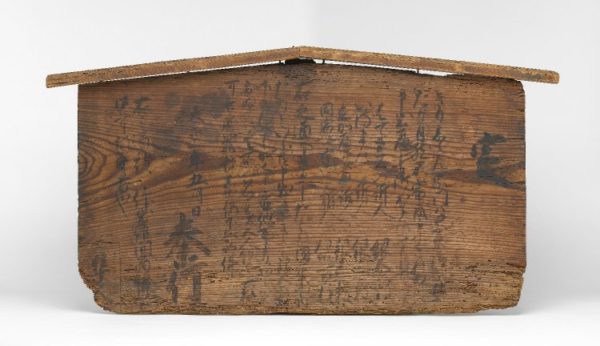

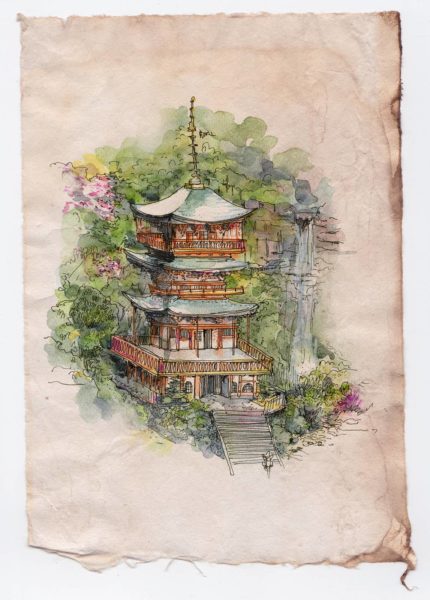

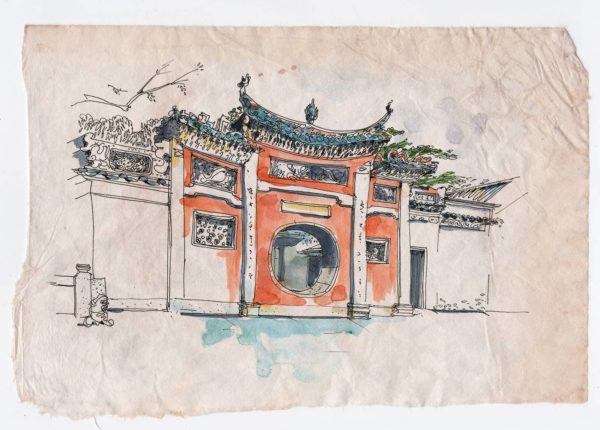

The São Catarina has arrived, after so many months, in the port of Nagasaki. The Yokoseura and Hirado-machi streets have a view of the harbour, while others look on the town. There are streets where we may rent rooms. As soon as we docked, the traders on my ship rushed off to secure these dwellings, using personal connections or the purse.

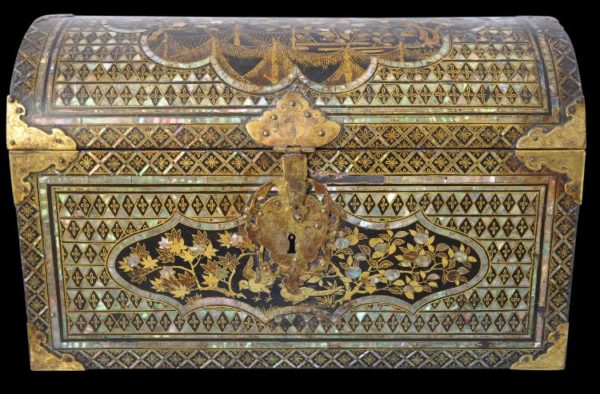

Their slaves and servants also secured accommodation, however lowly. For many months the Portuguese will eat and drink their way through Nagasaki. There will be no end to the deals and bartering. Menezes estimated that the traders will spend over 200,000 taels in the time we stay here; every month, more flows from their pockets to the Japanese.

It is no wonder the people of Nagasaki attend to us so carefully.

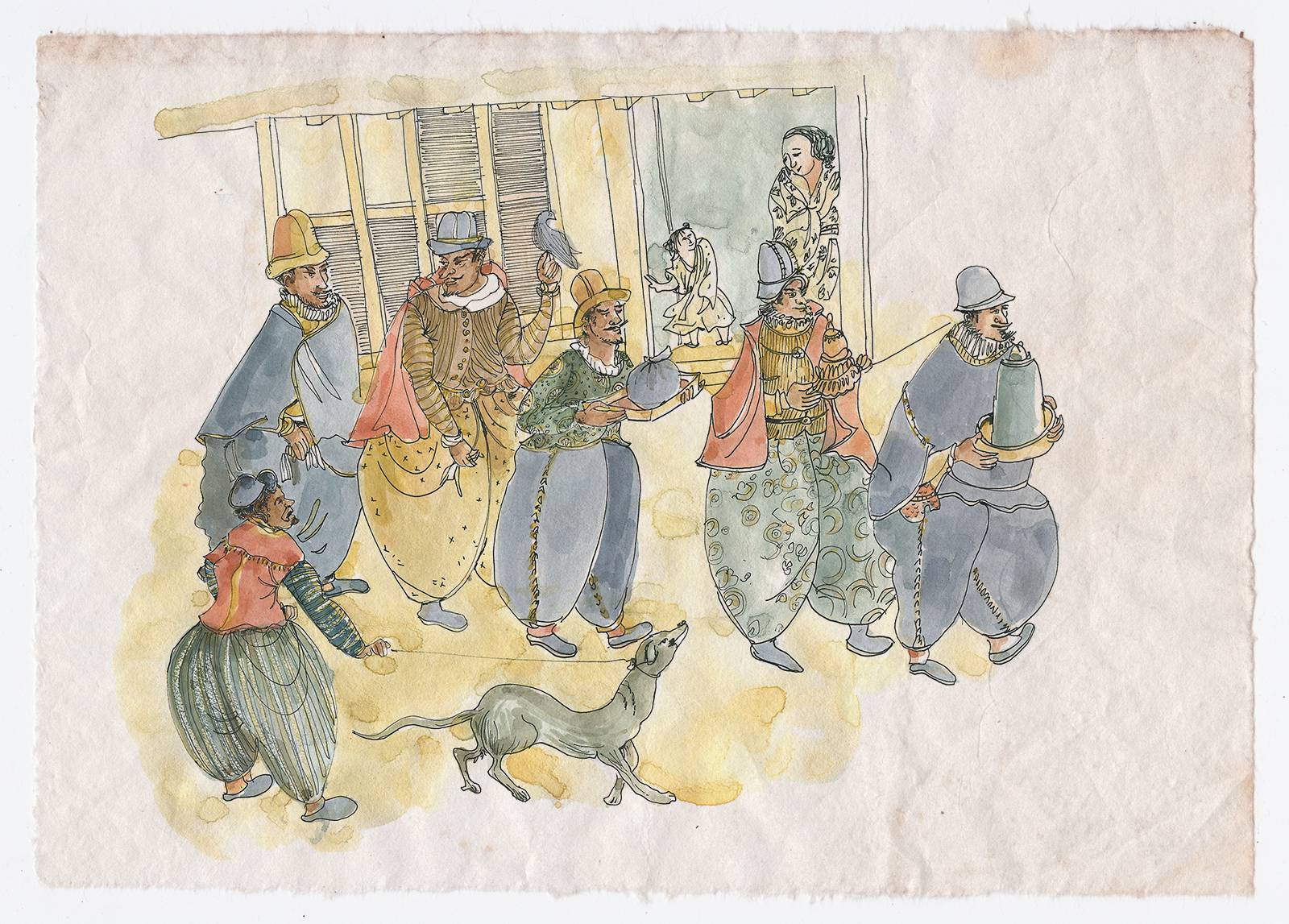

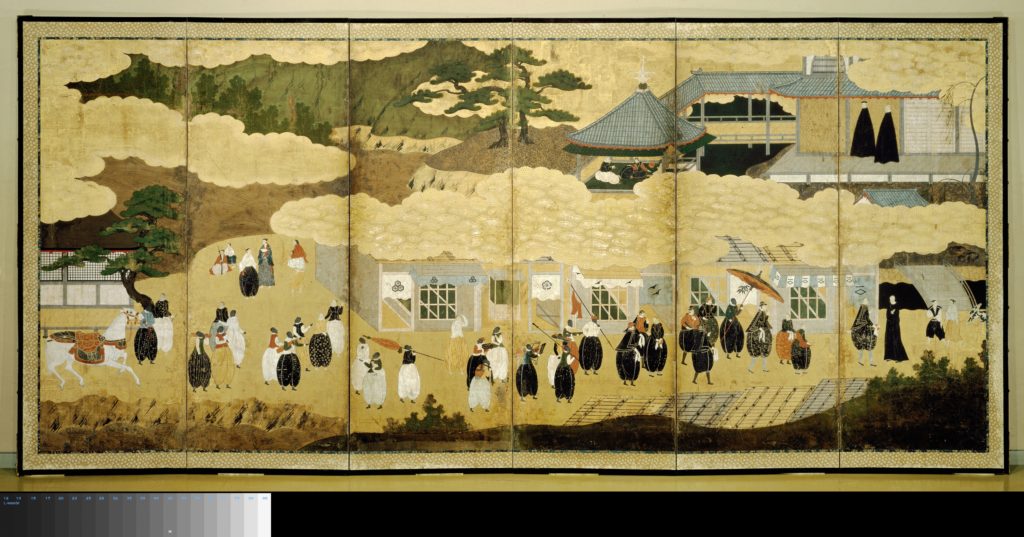

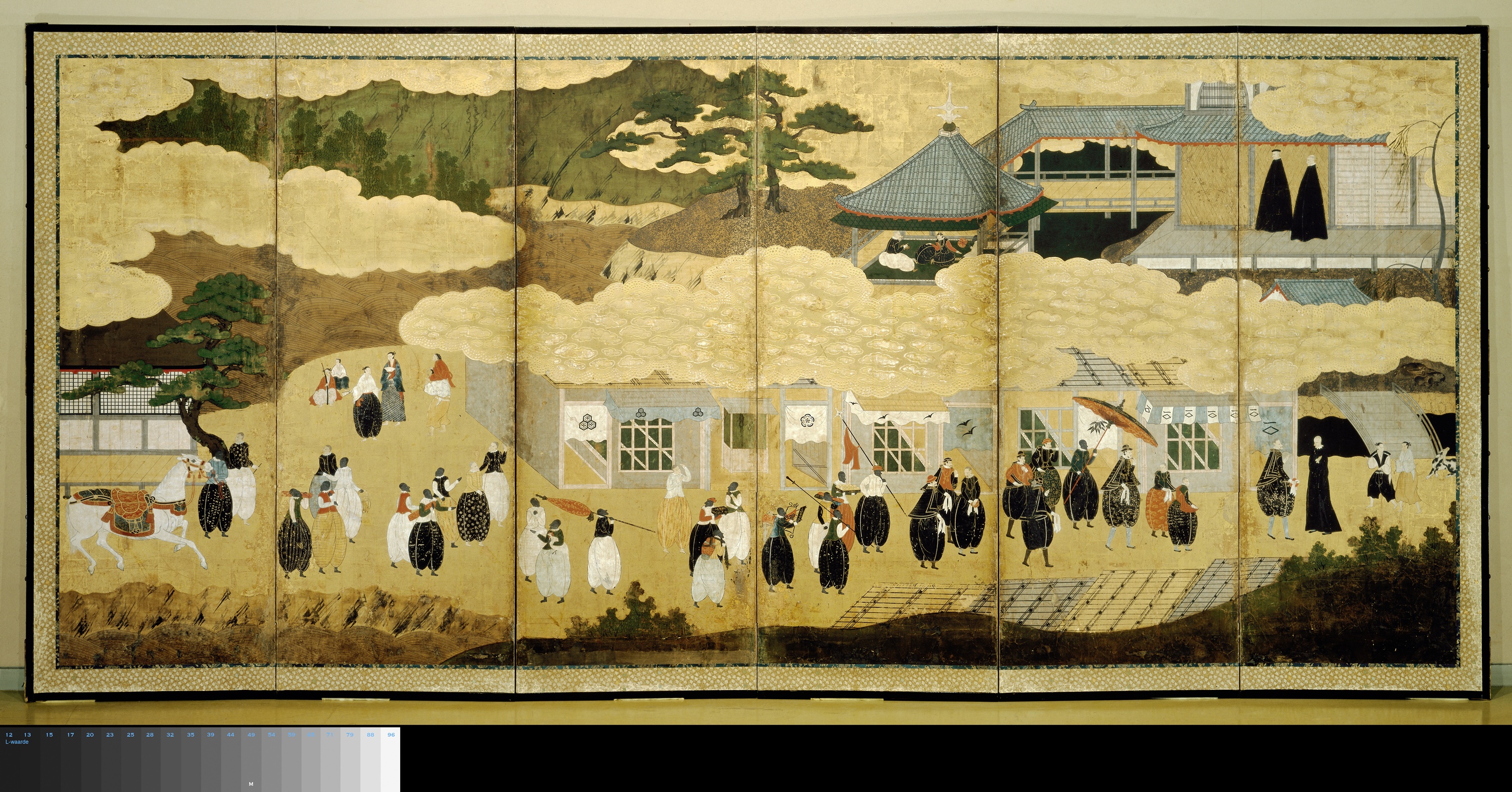

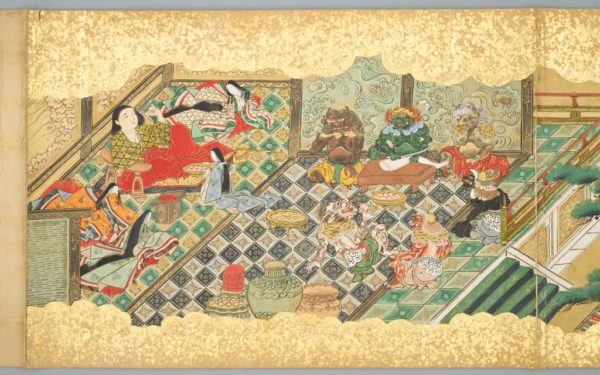

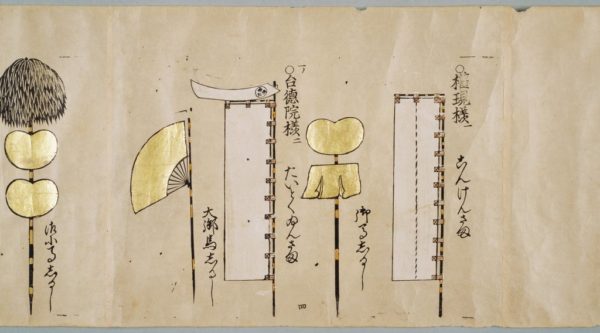

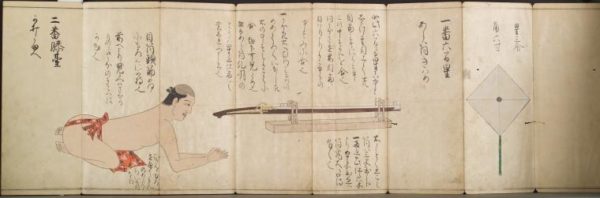

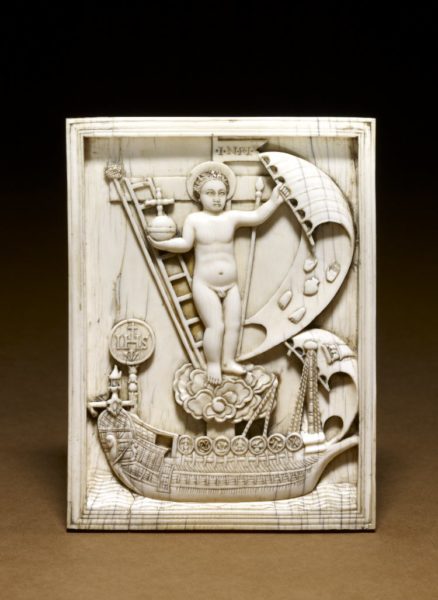

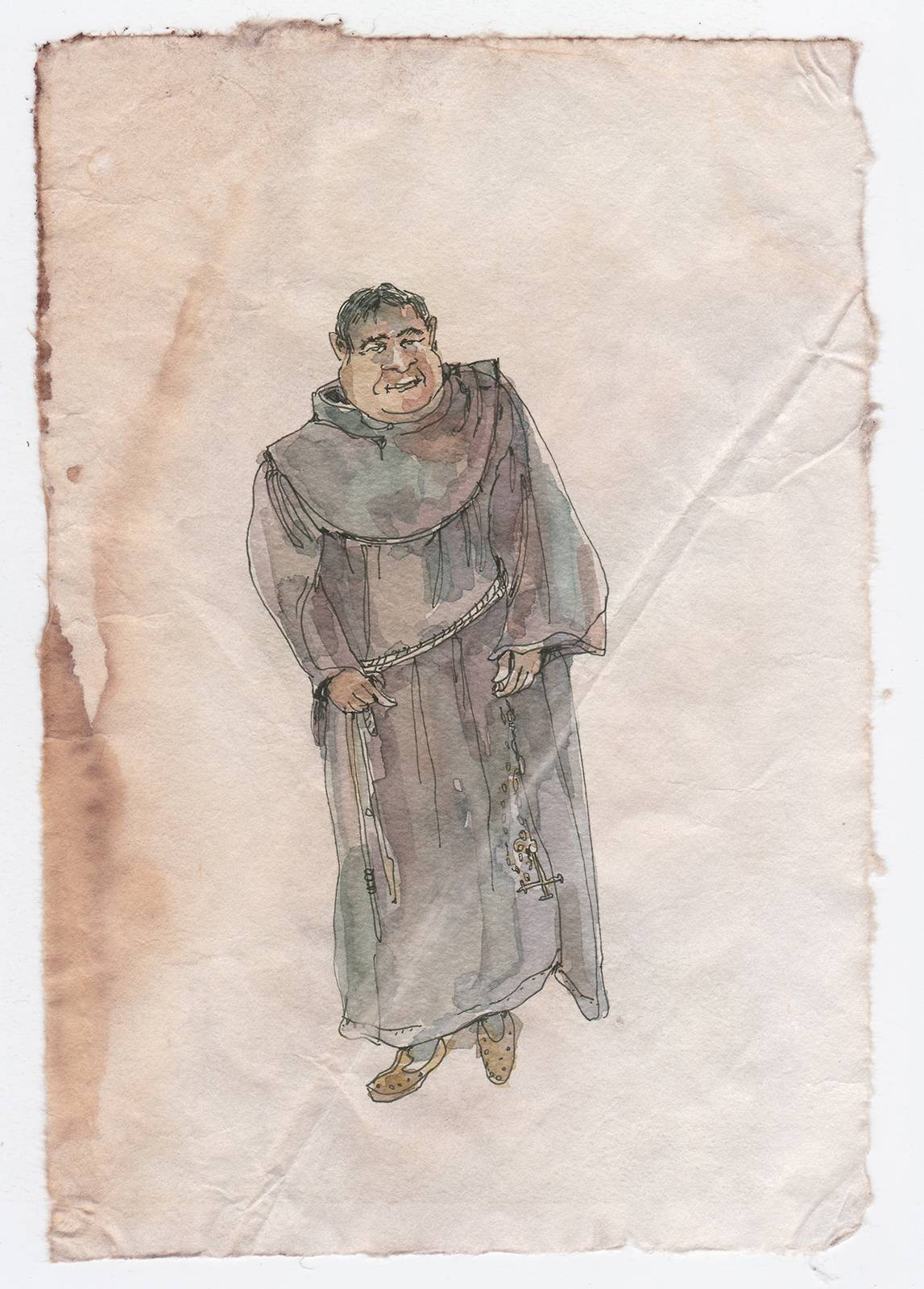

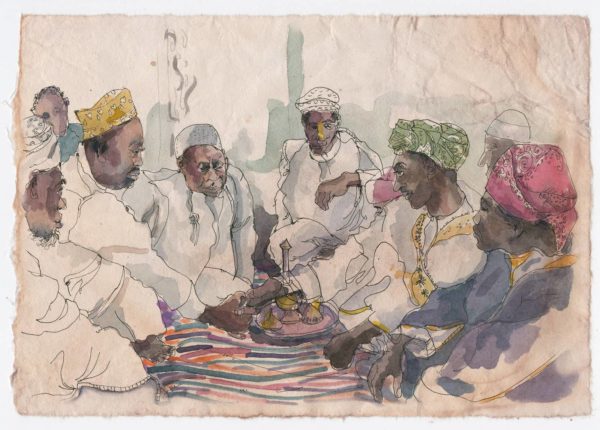

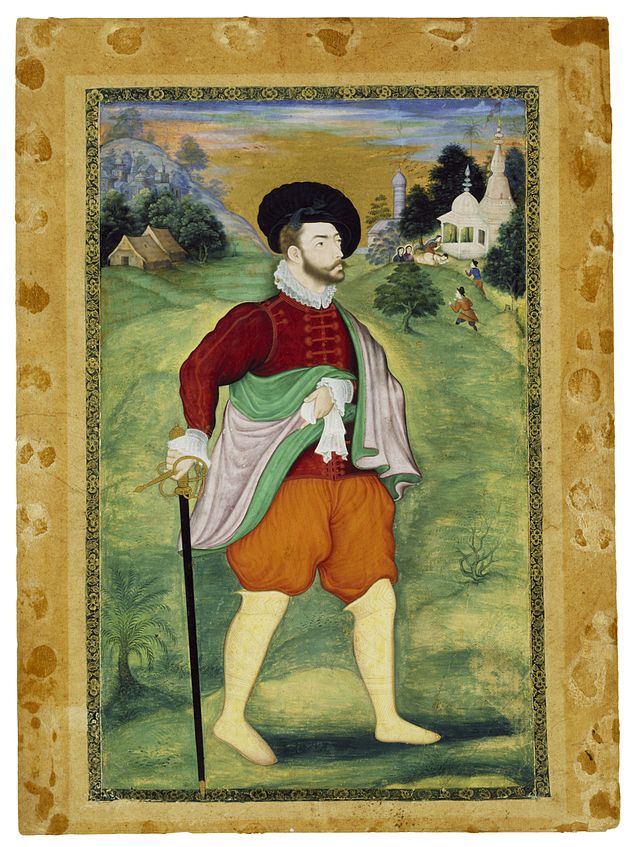

A festival occurred upon our arrival in Nagasaki; it was established and festive, full of life and color. Thousands of Japanese and Portuguese went together through the streets, singing and playing music on flutes and viols. There was much dancing. My men were glad to see the caboque on the streets. To have arrived safely from across the world is truly a cause for celebration. As the capitão mor, it was customary for me to prance down the avenues, followed by de Sousa carrying a huge brocade parasol. He performed the task admirably.

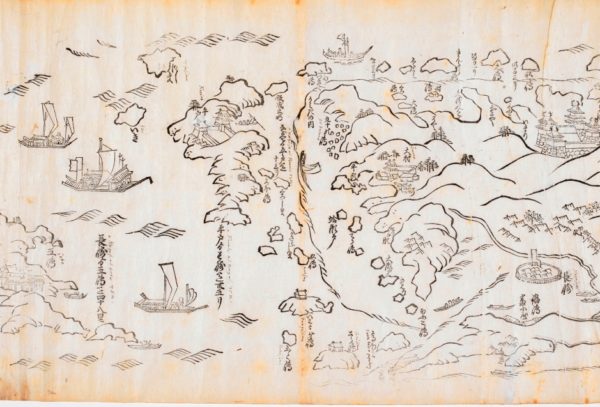

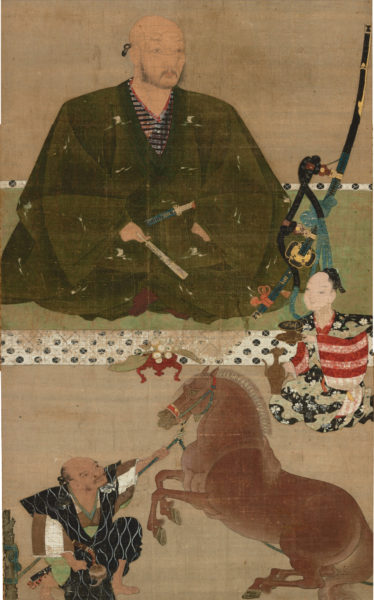

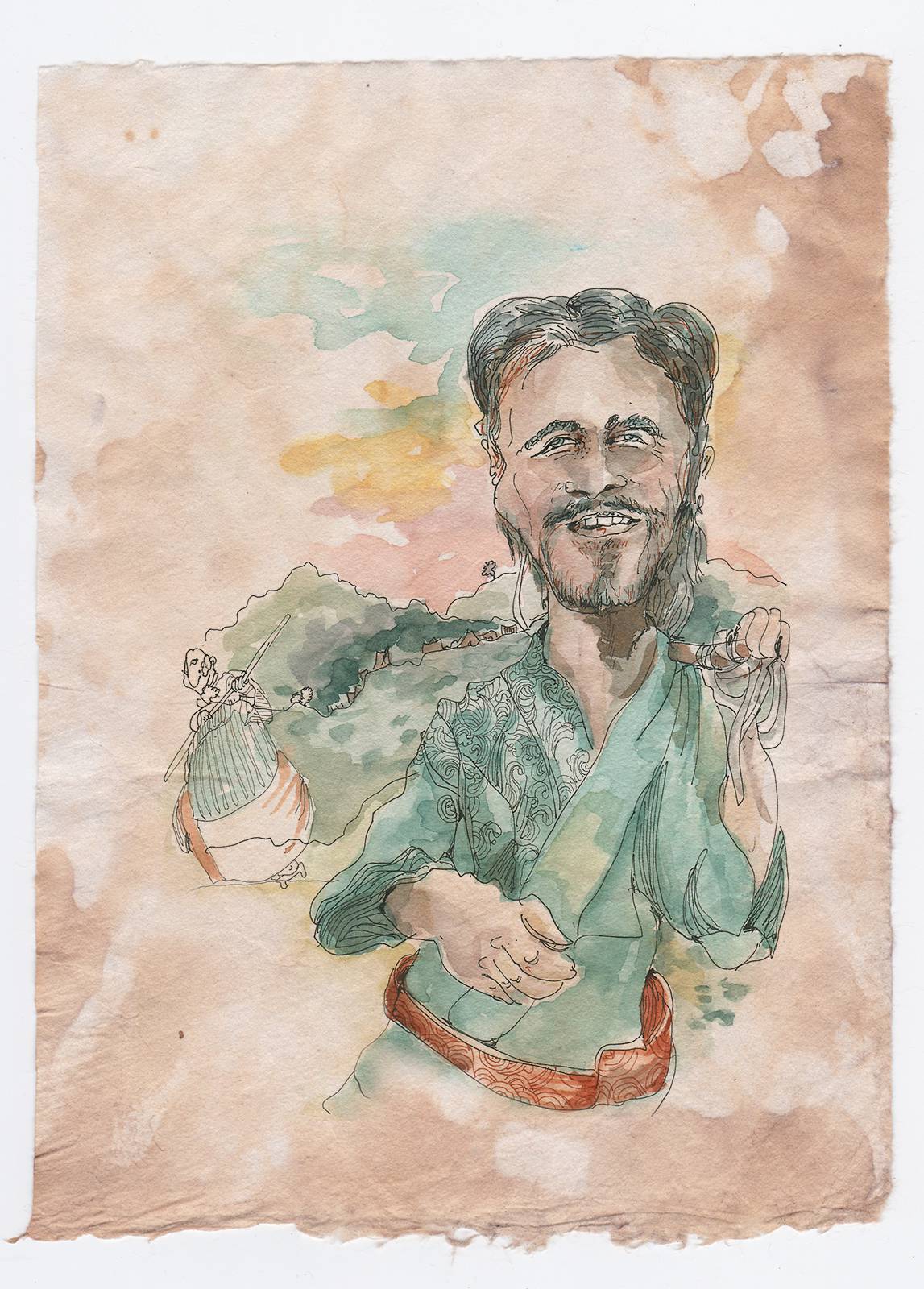

I saw some Japanese men painting our parade with small brushes; I must make an effort to meet them. I sent Fadrique, my cabin boy and servant, over to them with a drawing of mine; one of the translators went with him. He cannot speak a single word of Japanese, but has a bright face and trusting manner. Perhaps he can impress on them my interest in their art.